Free towels

In 2000 AVL (Atelier van Lieshout, established by the artist Joep van Lieshout) declared independence, calling its terrains in the port of Rotterdam the Free State of AVL-Ville. Collective thought and learning through practice would form the basis of communal life in this new state. Its citizens, the workers of AVL, were permitted to live in on the terrain if they would contribute to the construction of the infrastructure for inhabitation. Among other things, a chicken coop, pig sty, generator, and septic tank were built, as well as a crude form of public transport, involving a horse and cart. In other words, all that was necessary for self-sufficiency, down to the manufacture of weapons for self-defence.

But the defence system malfunctioned. Hardly a year later the Rotterdam authorities entered into AVL-Ville, requisitioning its famous company car, a Mercedes sedan converted into a pick-up truck, equipped with a home-made 57mm cannon. The police seized the gun, but decided to come back later for the car. By that time, however, it had already been bought up and towed away by the museum Boijmans van Beuningen.

Leading up to the genesis of AVL-Ville was the idea of autonomy that AVL had been developing for a while already, in its prototypes for mobile homes. Following in this vein, many of the designs of the free state were adapted to transportable units, shippable to other environments in the fashion of AVL-Ville franchises, and rapidly finding their way to prominent places in art exhibitions.

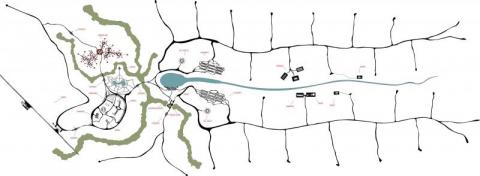

The closure of the free state marked a sinister new chapter in the productive output of AVL, in which the contagious optimism that characterised AVL-Ville was exchanged for a more dystopian approach to communal living. Cradle to cradle, for example, is a closed loop system that recycles human bodies, to be implemented in Joep van Lieshout's draft for a self-sufficient, green and 'zero-energy' town: Slave City. With a net profit of 7 billion Euros, this settlement could house 200.000 inhabitants who would work for seven hours each day in office jobs, and seven more hours on the agricultural fields, and who would sleep for the remaining seven hours after spending three hours of relaxation in the city's brothels.

There is an interesting discrepancy in the way these two different lines of “functional” design relate to reality. While the objects of AVL-Ville were actually put into practical effect in the attempt to construct an alternative, utopian society, those of Slave City skipped this step altogether before ending up in the habitat of the art exhibition. Does this mean, therefore, that the latter is further removed from reality? Or is Slave City's horror scenario the one that closest resembles our current situation, educating us about the dark side of western society in which the liberties of its citizens are sacrificed to pay for the luxuries of the few?

According to surveys on the social impact of the economical crisis in Spain, for example, there are 143.000 people whose net worth has exceeded 800.000 Euros, which are 16.000 more than in 2009. Meanwhile, approximately 20% of the population fall under the poverty threshold. So far, the crisis has lead to a rise of one million poor in Spain alone.

The initial stages of the economical crisis were analysed with great excitement. To some it looked as if the first cracks were appearing in a capitalist system that could not sustain itself. It was clear that this was a moment of change. But, a change to what? And what role would art play in it?

During the city council elections in Iceland in 2010, a new political party emerged, called The Best Party, formed by a group of artists, musicians and other cultural agents, lead by the comedian Jón Gnarr. The country, until then regarded as one of the most prosperous in the world, had been submerged in a financial nightmare, with thousands of citizens watching powerlessly as their debts rose to double the value of their belongings overnight.

The Best Party's political campaign was characterised by a bitter-sweet combination of idealism and black humour, with slogans such as: “Democracy is pretty good, but an effective democracy is best. That's why we want it”, and “We promise to stop corruption. We'll accomplish this by doing it openly”. They promised a polar bear for the zoo, free towels in the swimming pools and a drug-free parliament by 2020. “We are going to take humour to the streets”, its members proclaimed, “This is the hour of change. You have to choose”.

It may not have been the first party to turn its campaign into a satire of traditional politics, but it certainly was one of the most successful. The electorate cast its vote, and to the surprise and dismay of the established parties, The Best Party won the elections in Reykjavik. With four years of office ahead, it remains to be seen if it can live up to all of the expectations of the voters. But the election victory has already shown that there is no proposal or demand too unreasonable or outrageous, for it to make perfect sense under the present conditions of global financial meltdown and populist hyperboles.

Afterword 29/06/2011:

This article was first written in Spanish, and published in the Basque newspaper Gara in August 2010, as part of our series on art and politics. The chore of translating it might have been perpetually postponed, if recent events regarding cultural policies in The Netherlands hadn't imbued it with a new kind of relevance. The capacity of the recent protests against the cuts to mobilise so many people, paired with its failure to dissuade the government from its course of action, has left many of us with a shared sense of “What now?”. Here and there, the first calls for a continued resistance can already be heard. This time, however, it is about a resistance that looks beyond the culture sector's direct interests, towards reforming Dutch society as a whole, and wresting it back from the current government's fateful neoliberal grasp. We believe strongly that art can play a pivotal role in this transformation. But, if we are to take our cues from the examples presented in the article, it is time to leave self-effacing moderateness behind, stop being reasonable, and demand the impossible!

Iratxe Jaio and Klaas van Gorkum

Published in:

- Mugalari, el suplemento cultural del periódico Gara.

Recent comments