“We need spaces that allow people to struggle with each other for their meaning.”

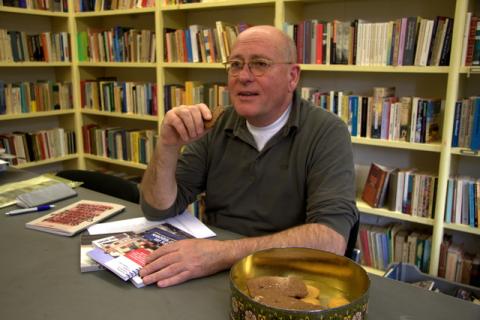

Independent researcher and consultant on the cutting edge of urbanism, Arnold Reijndorp has published books such as “In Search of New Public Domain”, an intensive quest to establish the parameters of a new public space which escapes the dominant cultural policies aimed at creating manageable, zero-friction environments. This October, Reijndorp paid a visit to Basque Country with the participants of a study trip organised by The Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design and Architecture.

One of the objectives of the study trip was to investigate different models of cultural policies. What insights have you brought back to the Netherlands?

Cultural policies can fill the gap that is left by a restructuring of the economy. We often forget that the social fabric of a city is conditioned by its economy. An industrial city is not just made up of a capitalist class, but also of a workforce whose daily life is determined by class struggle and trade union membership. So, when the economy changes, and this social fabric falls apart, it needs to be knitted together again.

Some cultural policies try to revive the economy by attracting tourism, others try to facilitate a creative class, attracting artists and other cultural agents to respond to the disparities within the social structure. This is the role usually taken up by bottom-up initiatives, which are often promoted by the official policy.

Most of the Dutch cities are trying to draw in creative professionals like this, but what I miss is an understanding of the creative city in a broader way, in the sense that it tries to explore and use the skills that already exist in the city. In the end, this emphasis on the importance of the creative class becomes a disqualification of an underclass that doesn't seem to count any more.

You have been in various European cities, can you compare any with what you have seen here?

One of the cities we visited was Skopje, the Macedonian capital, which, as in Basque Country, is embroiled in continuous nationalist identity politics. It was destroyed in the earthquake of 1963 and a modernist Japanese architect, Kenzo Tange was commissioned to make a reconstruction plan.

The modernist aesthetics of this restoration is seen by certain people as the continuation of a historical line from before the war, following the logic of an international city that acted as a bridge between eastern countries and the rest of Europe. Others see it as a break with that historical line, imposed by the communist clique that was in power at that moment. At the same time, the right wing party is trying to hide those modernist traces, building all kinds of big statues, promoting a new Macedonian identity that allegedly reaches all the way back to the historical period of Alexander the Great. Then there are the Albanians and Turks that have their own identity, and who do not participate in this discussion on the Macedonian identity.

It is a discussion that is not as complex as in Basque Country, where it takes place on many different levels. In Skopje, it often just takes the form of a struggle between populism and avant-gardism, with the latter being denounced as elitism promoted by a minority that pretends to know what the right style is.

And where does the Guggenheim stand in this?

The Guggenheim is not just a building, it is also an economical model that has affected society on many different levels. The question is whether the cultural agents that were there before, and that were part of a post-Franco identification strategy, could also have been part of an economical strategy to overcome the industrial crisis.

We could say that it was with the Guggenheim that the artistic scene got international legitimation. But I can imagine the mixed feelings. National identity, the international orientation of the art scene, the construction of a brand new cultural landscape, the landing of the Guggenheim in the middle of all this... It's a framework that makes Basque Country very complicated. The younger generation of cultural agents have to define themselves not only in relation to what was there before, but also in relation to the new institutions with which they have no affinity. In the Guggenheim they don't see this as a problem, since the building attracts tourists even with an empty program. But from the perspective of the art scene, I think it is.

What should be the role of a cultural policy?

Culture can help by extracting controversial issues from the political sphere and placing them in a less polarized field. But I don't know if this still works, because you could also say that the discussions in art always take place between the usual suspects, as the populists claim.

The architect Markus Miessen says that what we need is not more participation, but more space for conflict. In art, urbanism and architecture we are always trying to create spaces where people can meet each other, when the city is in fact a situation of perpetual conflict. So what we really need is space that allows people to neglect each other, or to struggle with each other for the meaning of those places.

The reconstruction of the waterfront in Bilbao, for example, is very smooth and pretty. People like that, of course, but the question is whether there is room for dissonance, such as the presence of homeless people. I'm not saying we should be making lousy places for lousy people, but I do think that some architecture is also a symbol for how it should and shouldn't be used, or for what people are preferred there, and what people are not preferred there.

What’s up, what’s down. Cultural catalysts in Urban Space

Every 3 years, the Fonds BKVB organises a study trip for architects and artists, designers or mediators whose work shows affinity with the public space. In the 2010 Study Trip, called “What’s up, what’s down. Cultural catalysts in Urban Space”, 25 participants have been invited to investigate the developement of European cities that have substituted their industrial past with a more cultural profile.

After visiting Skopje (Macedonia), Pristina (Kosovo), Tirana (Albania), Marseille (France), and the English cities Manchester, Leeds and Liverpool, they arrived to Basque Country. In three days, they were presented with a variety of perspectives from institutions and cultural agents such as: Bilbao Ria 2000, the Guggenheim museum, Iñaki Uriarte, Asier Mendizabal, Iskandar Rementeria, Iñaki Martínez de Albeniz, Anti- Liburudenda, Hiria Kolektiboa, consonni, Amaste, Saioa Olmo, Abisal, Krea, Artium, Plataforma Amarika, Miren Jaio and Leire Vergara, in an attempt to map the complex caleidoscope of relationships and histories that make up the cultural landscape of Bilbao and Vitoria.

The next phase of the trip will be to take the role of culture in the cities analysed, as scenarios from which to reflect on the Dutch model, which today finds itself in a different situation to when the group boarded their first plane. The new government, supported by the populist right, has announced drastic cuts in public funding for culture, undermining a system of subsidies that were emblematic of a welfare state that has lost credibility in the Netherlands. This part of the project will therefore have to deal with the possibility that it may have well been the last study trip organised by the institution.

Published in:

- Mugalari, el suplemento cultural del periódico Gara.

Recent comments